I would argue that this lack of cohesion in the South (which manifested itself in other ways as well) was a large factor in the Confederacy’s defeat. I would also argue that there was a lot more Confederate nationalism after there was no longer a Confederate nation, as evidenced by the aforementioned Rebel sentiment in places that were actually pro-Union.

After the war, the “Lost Cause ideology” took hold in the South (and the rest of the country.) In this worldview, the antebellum South was a romanticized place which its people fought nobly to defend, but which was doomed solely because of the North’s overwhelming military superiority (let me point out that in the American Revolution, the Texas War of Independence, and the Vietnam conflict, the losing side had overwhelming military superiority, yet this fact alone did not determine the outcomes of those conflicts.) Sure, there was such a thing as slavery, but it was not a major consideration. In some ways this worldview made the healing easier for the losers. We lost, but we lost nobly; and our cause was just, after all. It’s kind of embarrassing to say one’s great-great-grandfather died in a conflict that was mostly about keeping an oppressed people in chains.

This view has actually gained a lot more ground in the last decade or so. It is amazing that it took so long for anyone to catch the errors in that Virginia public school textbook a few months ago, the one which claimed that upwards of 100,000 blacks fought in the Confederate Army (half as many as in the Union!) That’s not true, of course. If there were any African Americans at all taking arms on behalf of the Confederacy they were a rare anomaly (See the various links at the end of this essay.) It turns out that the textbook author, a freelance writer rather than a trained historian, had gotten her information off the internet (specifically, from the Sons of Confederate Veterans website.)

As I said earlier, when I was younger I held the same beliefs—growing up in the South, one sort of absorbs them by osmosis. In college I learned that historians almost all present an opposite view, but that was not completely enough to make me re-examine what I thought I knew. It was actually when I reached graduate school that the last traces of Lost-Cause-Disorder were cleansed from my mind, and it was not due to historians or textbooks; it was due to my own research, and what I found in the archives.

Embarrassed descendants of the original Confederates may say the Civil War was not about slavery—and Confederate veterans, after the fact, might have said the same thing—but when the war was starting, Confederates and Federals alike knew what was causing it. Examples:

“Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery — the greatest material interest of the world. Its labor supplies the product which constitutes by far the largest and most important portions of the commerce of the earth. . . . A blow at slavery is a blow at commerce and civilization.” - Mississippi secession declaration, passed Jan. 9, 1861.

"One section of our country believes slavery is right and ought to be extended, while the other believes it is wrong and ought not to be extended. This is the only substantial dispute." –Abraham Lincoln, First Inaugural Address

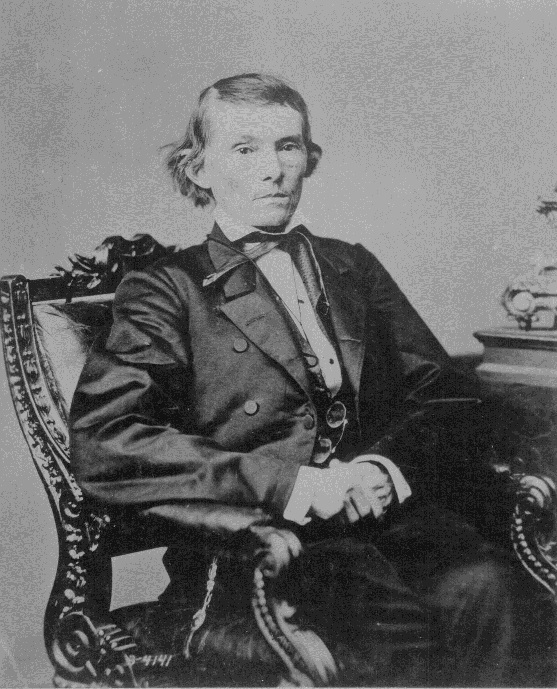

And then there is this, from Confederate Vice-President Alexander Stephens in a speech delivered in Savannah, Georgia, on March 21, 1861:

I would argue that this lack of cohesion in the South (which manifested itself in other ways as well) was a large factor in the Confederacy’s defeat. I would also argue that there was a lot more Confederate nationalism after there was no longer a Confederate nation, as evidenced by the aforementioned Rebel sentiment in places that were actually pro-Union.

After the war, the “Lost Cause ideology” took hold in the South (and the rest of the country.) In this worldview, the antebellum South was a romanticized place which its people fought nobly to defend, but which was doomed solely because of the North’s overwhelming military superiority (let me point out that in the American Revolution, the Texas War of Independence, and the Vietnam conflict, the losing side had overwhelming military superiority, yet this fact alone did not determine the outcomes of those conflicts.) Sure, there was such a thing as slavery, but it was not a major consideration. In some ways this worldview made the healing easier for the losers. We lost, but we lost nobly; and our cause was just, after all. It’s kind of embarrassing to say one’s great-great-grandfather died in a conflict that was mostly about keeping an oppressed people in chains.

This view has actually gained a lot more ground in the last decade or so. It is amazing that it took so long for anyone to catch the errors in that Virginia public school textbook a few months ago, the one which claimed that upwards of 100,000 blacks fought in the Confederate Army (half as many as in the Union!) That’s not true, of course. If there were any African Americans at all taking arms on behalf of the Confederacy they were a rare anomaly (See the various links at the end of this essay.) It turns out that the textbook author, a freelance writer rather than a trained historian, had gotten her information off the internet (specifically, from the Sons of Confederate Veterans website.)

As I said earlier, when I was younger I held the same beliefs—growing up in the South, one sort of absorbs them by osmosis. In college I learned that historians almost all present an opposite view, but that was not completely enough to make me re-examine what I thought I knew. It was actually when I reached graduate school that the last traces of Lost-Cause-Disorder were cleansed from my mind, and it was not due to historians or textbooks; it was due to my own research, and what I found in the archives.

Embarrassed descendants of the original Confederates may say the Civil War was not about slavery—and Confederate veterans, after the fact, might have said the same thing—but when the war was starting, Confederates and Federals alike knew what was causing it. Examples:

“Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery — the greatest material interest of the world. Its labor supplies the product which constitutes by far the largest and most important portions of the commerce of the earth. . . . A blow at slavery is a blow at commerce and civilization.” - Mississippi secession declaration, passed Jan. 9, 1861.

"One section of our country believes slavery is right and ought to be extended, while the other believes it is wrong and ought not to be extended. This is the only substantial dispute." –Abraham Lincoln, First Inaugural Address

And then there is this, from Confederate Vice-President Alexander Stephens in a speech delivered in Savannah, Georgia, on March 21, 1861:

“The new constitution has put at rest, forever, all the agitating questions relating to our peculiar institution African slavery as it exists amongst us the proper status of the negro in our form of civilization. This was the immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution. Jefferson in his forecast, had anticipated this, as the "rock upon which the old Union would split." He was right. What was conjecture with him, is now a realized fact. But whether he fully comprehended the great truth upon which that rock stood and stands, may be doubted. The prevailing ideas entertained by him and most of the leading statesmen at the time of the formation of the old constitution, were that the enslavement of the African was in violation of the laws of nature; that it was wrong in principle, socially, morally, and politically. It was an evil they knew not well how to deal with, but the general opinion of the men of that day was that, somehow or other in the order of Providence, the institution would be evanescent and pass away. This idea, though not incorporated in the constitution, was the prevailing idea at that time. The constitution, it is true, secured every essential guarantee to the institution while it should last, and hence no argument can be justly urged against the constitutional guarantees thus secured, because of the common sentiment of the day. Those ideas, however, were fundamentally wrong. They rested upon the assumption of the equality of races. This was an error. It was a sandy foundation, and the government built upon it fell when the "storm came and the wind blew."

Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its corner- stone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth. This truth has been slow in the process of its development, like all other truths in the various departments of science. It has been so even amongst us. Many who hear me, perhaps, can recollect well, that this truth was not generally admitted, even within their day. The errors of the past generation still clung to many as late as twenty years ago. Those at the North, who still cling to these errors, with a zeal above knowledge, we justly denominate fanatics. All fanaticism springs from an aberration of the mind from a defect in reasoning. It is a species of insanity. One of the most striking characteristics of insanity, in many instances, is forming correct conclusions from fancied or erroneous premises; so with the anti-slavery fanatics. Their conclusions are right if their premises were. They assume that the negro is equal, and hence conclude that he is entitled to equal privileges and rights with the white man. If their premises were correct, their conclusions would be logical and just but their premise being wrong, their whole argument fails. I recollect once of having heard a gentleman from one of the northern States, of great power and ability, announce in the House of Representatives, with imposing effect, that we of the South would be compelled, ultimately, to yield upon this subject of slavery, that it was as impossible to war successfully against a principle in politics, as it was in physics or mechanics. That the principle would ultimately prevail. That we, in maintaining slavery as it exists with us, were warring against a principle, a principle founded in nature, the principle of the equality of men. The reply I made to him was, that upon his own grounds, we should, ultimately, succeed, and that he and his associates, in this crusade against our institutions, would ultimately fail. The truth announced, that it was as impossible to war successfully against a principle in politics as it was in physics and mechanics, I admitted; but told him that it was he, and those acting with him, who were warring against a principle. They were attempting to make things equal which the Creator had made unequal.

In the conflict thus far, success has been on our side, complete throughout the length and breadth of the Confederate States. It is upon this, as I have stated, our social fabric is firmly planted; and I cannot permit myself to doubt the ultimate success of a full recognition of this principle throughout the civilized and enlightened world.

As I have stated, the truth of this principle may be slow in development, as all truths are and ever have been, in the various branches of science. It was so with the principles announced by Galileo it was so with Adam Smith and his principles of political economy. It was so with Harvey, and his theory of the circulation of the blood. It is stated that not a single one of the medical profession, living at the time of the announcement of the truths made by him, admitted them. Now, they are universally acknowledged. May we not, therefore, look with confidence to the ultimate universal acknowledgment of the truths upon which our system rests? It is the first government ever instituted upon the principles in strict conformity to nature, and the ordination of Providence, in furnishing the materials of human society. Many governments have been founded upon the principle of the subordination and serfdom of certain classes of the same race; such were and are in violation of the laws of nature. Our system commits no such violation of nature's laws. With us, all of the white race, however high or low, rich or poor, are equal in the eye of the law. Not so with the negro. Subordination is his place. He, by nature, or by the curse against Canaan, is fitted for that condition which he occupies in our system. The architect, in the construction of buildings, lays the foundation with the proper material-the granite; then comes the brick or the marble. The substratum of our society is made of the material fitted by nature for it, and by experience we know that it is best, not only for the superior, but for the inferior race, that it should be so. It is, indeed, in conformity with the ordinance of the Creator. It is not for us to inquire into the wisdom of His ordinances, or to question them. For His own purposes, He has made one race to differ from another, as He has made "one star to differ from another star in glory." The great objects of humanity are best attained when there is conformity to His laws and decrees, in the formation of governments as well as in all things else. Our confederacy is founded upon principles in strict conformity with these laws. This stone which was rejected by the first builders "is become the chief of the corner" the real "corner-stone" in our new edifice. I have been asked, what of the future? It has been apprehended by some that we would have arrayed against us the civilized world. I care not who or how many they may be against us, when we stand upon the eternal principles of truth, if we are true to ourselves and the principles for which we contend, we are obliged to, and must triumph.”

It is difficult to read that speech and still argue that the Civil War was not about slavery. What really got to me, personally, though, was reading contemporary newspaper accounts from my own home region and discovering prominent citizens (like Judge Sam Gardenhire, one of the biggest slaveholders in the Upper Cumberland region of Tennessee) making the very same arguments as Stephens. The Confederate VP was not some firebrand saying things that no one in his audience agreed with—quite the opposite.

The documents verify what professional historians will tell you. Slavery caused the Civil War.

But what does it really matter, you might ask.

If more and more people become convinced that the Civil War was not about slavery, the public perception will eventually be that slavery was really not so bad. The principles which propelled the abolition of slavery, and the lived experience of all those who suffered it, will be disregarded. What is to stop people from then saying that the folks who opposed Desegregation were not really racists, they were just trying to protect states’ rights? What is to prevent some from saying, and convincing the public, that most African Americans were really on the side of the segregationists, and many of them fought alongside the local Jim Crow authorities against all those Northern interlopers and communists who were saying “Freedom Now”? It’s the same thing—and it would imply that segregation was not that bad, and that the social changes which were made in the Civil Rights Era were not really necessary or important. Why, it was all about the federal government trying to enforce its agenda on state governments and local businesses (thanks to Rand Paul, this example is not completely hypothetical.)

This is serious business. It really matters. So think about this: if it really bothers you that someone says a war fought 150 years ago was about slavery—why? What is your investment? Because if you are a historian, your investment is in the truth.

Read more:

“150 Years after Fort Sumter: Why We’re Still Fighting the Civil War” by David Von Drehle

“Fort Sumter: The Civil War Begins” by Fergus M. Bordewich

“The Myth of the Black Confederate” by Bruce Levine

“A Union Divided: South Split on U.S. Civil War Legacy” by Claire Suddath

“Five Myths About Why the South Seceded” by James Loewen

Alexander Stephens’ “Cornerstone” speech, in full:

“The new constitution has put at rest, forever, all the agitating questions relating to our peculiar institution African slavery as it exists amongst us the proper status of the negro in our form of civilization. This was the immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution. Jefferson in his forecast, had anticipated this, as the "rock upon which the old Union would split." He was right. What was conjecture with him, is now a realized fact. But whether he fully comprehended the great truth upon which that rock stood and stands, may be doubted. The prevailing ideas entertained by him and most of the leading statesmen at the time of the formation of the old constitution, were that the enslavement of the African was in violation of the laws of nature; that it was wrong in principle, socially, morally, and politically. It was an evil they knew not well how to deal with, but the general opinion of the men of that day was that, somehow or other in the order of Providence, the institution would be evanescent and pass away. This idea, though not incorporated in the constitution, was the prevailing idea at that time. The constitution, it is true, secured every essential guarantee to the institution while it should last, and hence no argument can be justly urged against the constitutional guarantees thus secured, because of the common sentiment of the day. Those ideas, however, were fundamentally wrong. They rested upon the assumption of the equality of races. This was an error. It was a sandy foundation, and the government built upon it fell when the "storm came and the wind blew."

Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its corner- stone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth. This truth has been slow in the process of its development, like all other truths in the various departments of science. It has been so even amongst us. Many who hear me, perhaps, can recollect well, that this truth was not generally admitted, even within their day. The errors of the past generation still clung to many as late as twenty years ago. Those at the North, who still cling to these errors, with a zeal above knowledge, we justly denominate fanatics. All fanaticism springs from an aberration of the mind from a defect in reasoning. It is a species of insanity. One of the most striking characteristics of insanity, in many instances, is forming correct conclusions from fancied or erroneous premises; so with the anti-slavery fanatics. Their conclusions are right if their premises were. They assume that the negro is equal, and hence conclude that he is entitled to equal privileges and rights with the white man. If their premises were correct, their conclusions would be logical and just but their premise being wrong, their whole argument fails. I recollect once of having heard a gentleman from one of the northern States, of great power and ability, announce in the House of Representatives, with imposing effect, that we of the South would be compelled, ultimately, to yield upon this subject of slavery, that it was as impossible to war successfully against a principle in politics, as it was in physics or mechanics. That the principle would ultimately prevail. That we, in maintaining slavery as it exists with us, were warring against a principle, a principle founded in nature, the principle of the equality of men. The reply I made to him was, that upon his own grounds, we should, ultimately, succeed, and that he and his associates, in this crusade against our institutions, would ultimately fail. The truth announced, that it was as impossible to war successfully against a principle in politics as it was in physics and mechanics, I admitted; but told him that it was he, and those acting with him, who were warring against a principle. They were attempting to make things equal which the Creator had made unequal.

In the conflict thus far, success has been on our side, complete throughout the length and breadth of the Confederate States. It is upon this, as I have stated, our social fabric is firmly planted; and I cannot permit myself to doubt the ultimate success of a full recognition of this principle throughout the civilized and enlightened world.

As I have stated, the truth of this principle may be slow in development, as all truths are and ever have been, in the various branches of science. It was so with the principles announced by Galileo it was so with Adam Smith and his principles of political economy. It was so with Harvey, and his theory of the circulation of the blood. It is stated that not a single one of the medical profession, living at the time of the announcement of the truths made by him, admitted them. Now, they are universally acknowledged. May we not, therefore, look with confidence to the ultimate universal acknowledgment of the truths upon which our system rests? It is the first government ever instituted upon the principles in strict conformity to nature, and the ordination of Providence, in furnishing the materials of human society. Many governments have been founded upon the principle of the subordination and serfdom of certain classes of the same race; such were and are in violation of the laws of nature. Our system commits no such violation of nature's laws. With us, all of the white race, however high or low, rich or poor, are equal in the eye of the law. Not so with the negro. Subordination is his place. He, by nature, or by the curse against Canaan, is fitted for that condition which he occupies in our system. The architect, in the construction of buildings, lays the foundation with the proper material-the granite; then comes the brick or the marble. The substratum of our society is made of the material fitted by nature for it, and by experience we know that it is best, not only for the superior, but for the inferior race, that it should be so. It is, indeed, in conformity with the ordinance of the Creator. It is not for us to inquire into the wisdom of His ordinances, or to question them. For His own purposes, He has made one race to differ from another, as He has made "one star to differ from another star in glory." The great objects of humanity are best attained when there is conformity to His laws and decrees, in the formation of governments as well as in all things else. Our confederacy is founded upon principles in strict conformity with these laws. This stone which was rejected by the first builders "is become the chief of the corner" the real "corner-stone" in our new edifice. I have been asked, what of the future? It has been apprehended by some that we would have arrayed against us the civilized world. I care not who or how many they may be against us, when we stand upon the eternal principles of truth, if we are true to ourselves and the principles for which we contend, we are obliged to, and must triumph.”

It is difficult to read that speech and still argue that the Civil War was not about slavery. What really got to me, personally, though, was reading contemporary newspaper accounts from my own home region and discovering prominent citizens (like Judge Sam Gardenhire, one of the biggest slaveholders in the Upper Cumberland region of Tennessee) making the very same arguments as Stephens. The Confederate VP was not some firebrand saying things that no one in his audience agreed with—quite the opposite.

The documents verify what professional historians will tell you. Slavery caused the Civil War.

But what does it really matter, you might ask.

If more and more people become convinced that the Civil War was not about slavery, the public perception will eventually be that slavery was really not so bad. The principles which propelled the abolition of slavery, and the lived experience of all those who suffered it, will be disregarded. What is to stop people from then saying that the folks who opposed Desegregation were not really racists, they were just trying to protect states’ rights? What is to prevent some from saying, and convincing the public, that most African Americans were really on the side of the segregationists, and many of them fought alongside the local Jim Crow authorities against all those Northern interlopers and communists who were saying “Freedom Now”? It’s the same thing—and it would imply that segregation was not that bad, and that the social changes which were made in the Civil Rights Era were not really necessary or important. Why, it was all about the federal government trying to enforce its agenda on state governments and local businesses (thanks to Rand Paul, this example is not completely hypothetical.)

This is serious business. It really matters. So think about this: if it really bothers you that someone says a war fought 150 years ago was about slavery—why? What is your investment? Because if you are a historian, your investment is in the truth.

Read more:

“150 Years after Fort Sumter: Why We’re Still Fighting the Civil War” by David Von Drehle

“Fort Sumter: The Civil War Begins” by Fergus M. Bordewich

“The Myth of the Black Confederate” by Bruce Levine

“A Union Divided: South Split on U.S. Civil War Legacy” by Claire Suddath

“Five Myths About Why the South Seceded” by James Loewen

Alexander Stephens’ “Cornerstone” speech, in full: